“We want to gain official recognition of the historic significance of Champagne production in Reims and Epernay”, our guide at Tattinger tells me. “So some of the houses came together to start a candidature for UNESCO status for the vineyards, the Champagne maisons and the caves”.

So, what makes Champagne so special?

PRODUCTION

Almost every bottle of Champagne you find on supermarket shelves will have been at least three years in the making.

Viticulture

As for all French wines, strict rules govern Champagne production. The vineyards around Reims and Epernay divide into three principal zones, within which each village is categorised into a cru according to its quality. Each of these zones is best suited to growing one of the grapes that may be used in Champagne production: Chardonnay (Côte des Blancs), Pinot Noir (Montagne de Reims) and Pinot Meunier (Vallée de la Marne). Put rather simply, Chardonnay adds lightness to the blend, Pinot Meunier gives the fruitiness and Pinot Noir adds structure.

And yes, the latter two are red grapes. Think about eating a grape: the juice is always clear. The colour of a red wine comes from contact with the grape skins, which is avoided here by very gentle pressing and running off the juice straight away.

First fermentation

Once picked and pressed the grape juice, or “must”, from each village is kept separate and the first fermentation (turning the juice into wine) will occur in modern stainless steel vats to preserve the natural fruit flavours. Yeast is added to start the process, converting the natural sugars to alcohol and carbon dioxide, which is allowed to escape.

Most houses also opt for a process called malolactic fermentation, where the conversion of malic acid to lactic acid softens the acidity and rounds the wine.

Blending

At the end of the first fermentation, the cellar master will have numerous vats of different still white wines, each showing different characteristics according to their site and grape variety. Now comes the fun part: tasting each one and deciding on how to blend them. For most Champagnes, the aim of blending is to maintain the house style year-on-year. Using still base wines from previous years is also permitted, which is why you won’t find a year on most Champagne bottles as you would other wines.

The very best wines from the grand cru villages may be used for the houses’ prestige blends, while in the odd excellent year a vintage Champagne may also be created using grapes only from that year’s harvest.

Second fermentation

The wine is now bottled, and a liquer de tirage is added to each one. This contains yeast and sugar to restart the fermentation process. Although unlike in the first fermentation, the bottles are sealed with a metal cap (just like a beer bottle cap) so the carbon dioxide cannot escape and has to dissolve into the wine creating the bubbles.

Ageing

Once the yeast has converted all of the sugar in the wine, it dies and sinks to the bottom of the bottle as a deposit known as lees. It is the lees that give Champagne its finesse and complex, sometimes biscuity flavours. Prosecco, for example, undergoes its second fermentation in a tank without any lees contact.

A basic Champagne is required by law to rest on lees for 15 months, but most houses will leave it for 3 years. Champagnes, therefore, should not be aged at home; this has already been done by the house and further ageing may lead to oxidation and diminished quality.

Remuage or “riddling”

Once the Champagne has aged, the dead yeast must be removed by a process known as remuage. Traditionally, bottles are stored in wooden racks and this is done by a remueur, who twists each bottle a quarter turn and raises it upwards a little more each day. A skilled remueur can turn up to 38,000 bottles a day. Eventually, the bottle will be nearly perpendicular with the cap at the bottom and a plug of yeast above it. This takes a remueur – a few of which are still employed by Champagne houses to turn a small portion of their bottles – up to eight weeks but machines can now complete the task in under two.

Disgorgement

The neck of the Champagne bottle is plunged into a freezing chemical solution before the cap is removed, allowing the pressure to expel the plug of yeast. A little Champagne is lost, but this is compensated by the liquer d’expédition, a solution of sugar and wine. This dosage determines the sweetness of the final wine, most often “Brut” (7–10g of sugar), but sometimes a little sweeter. Over time tastes have changed greatly; two-hundred years ago Champagnes may have had up to 300g of sugar added, but today there’s a growing trend for bone dry or zero dosage wines.

THE CELLARS

I made it to two houses during my time in Reims: Tattinger and G.H. Mumm. There’s nothing like drinking a glass of wine on the same spot where it’s been produced for centuries.

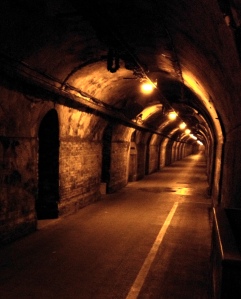

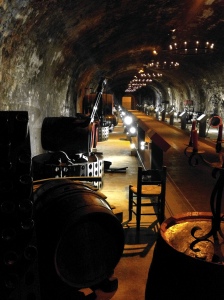

I can only apologise for the shocking photos. Most are from my iPhone, and the rest taken on the move, without flash, in low lighting.

Tattinger

• Production was begun on this site by monks of the now destroyed Abbaye Saint Nicaise. Part of the abbey’s crypts and vaults make up the caves used today. The rest lie in Roman chalk pits; just two houses in Reims have caves within these. At their deepest, the cellars are 20m underground where the temperature remains a steady 8oC.

• Tattinger hire 800 workers to pick 4,000kg of grapes at harvest time.

• Their standard Brut Reserve is unusually a Chardonnay dominated Champagne, with 40% white grapes used. It accounts for 80% of their production.

The only disappointment? The tasting. After an insightful and atmospheric tour, we were handed a glass of bubbly with no explanation or tasting advice, then rushed out (via the “boutique” desk) as quickly as they could manage.

The cellars, however, are just fantastic. Imagine strolling through past thousands upon thousands of bottles down dimly-lit, cool and echoey caverns, while above you can see the small surface entry points used by Roman miners. Elsewhere, you can spot the old steps that once led to the abbey, while salvaged doors have been incorporated into the modern layout.

G.H. Mumm

• Mumm have 218 hectares of vineyards, 98% of which is grand and premier cru, but this only makes up a third of their needs; the rest of the grapes are bought in from private growers.

• The Mumm signature is “intensity and freshness” and their standard cuvee, the Cordon Rouge, is Pinot Noir dominated (40%).

• Mumm is the brand you’ll see on the Formula 1 podium.

There’s no getting away from the fact that Mumm’s cellars can’t compete for atmosphere, but their tour is much more informative and gives greater insight into the winemaking process. They’ve preserved parts of their history throughout: the tour begins with the a walk past the huge barrels and concrete vats once used for the first fermentation and ends in a small “museum” of more prosaic items like early machines used in disgorgement.

When it comes to the tasting at Mumm, you also have a greater choice, ranging in price from a glass of Cordon Rouge to a well-orchestrated tasting flight through some of their finest Champagnes.

THE CHAMPAGNE

So, while I still love British fizz, and feel very strongly about supporting our brilliant vineyards, I suppose I now understand a little better why the Champagne producers feel their product has a superior history, if not quality.

By law, Champagne already may only be made in this region. A wine made from the same grapes and by the same process elsewhere may only be described as being made by the méthode champenoise or méthode traditionnelle.

When it comes to Champagne, imitation is perhaps not the sincerest form of flattery.

* Disclosure: as the primary purpose of my visit was to update the coverage of the Champagne houses for the Rough Guide to Europe on a Budget, both very kindly offered me a press ticket.